The Foundations to Optimal Digestion: A Journey Through Our Digestive System

Today, on How Our Digestion Works, we're going to take a journey through our digestive system. We'll see and feel what happens if you got eaten!

For a moment, pretend you're a piece of food. Let's say you're a lovely piece of broccoli. You got a charming tuft of the florets on top, and some of the robust and fibrous stock underneath. You're perfectly bitesize, covered with a little bit of butter and just a dash of salt and pepper.

Lightly steamed, the salt and the heat start breaking down your fibers, leaving a little bit of crunch, and still soft enough to enjoy.

And that's where our digestion begins. Whether we eat something cooked or raw, we decide how early digestion begins. When we cook something a little bit, like lightly steamed broccoli, we start breaking down the tough fibers and begin to liberate the nutrients. But, we're not cooking it enough that we start turning it to mush and destroying the lovely chlorophyll and helpful enzymes that aid our digestion.

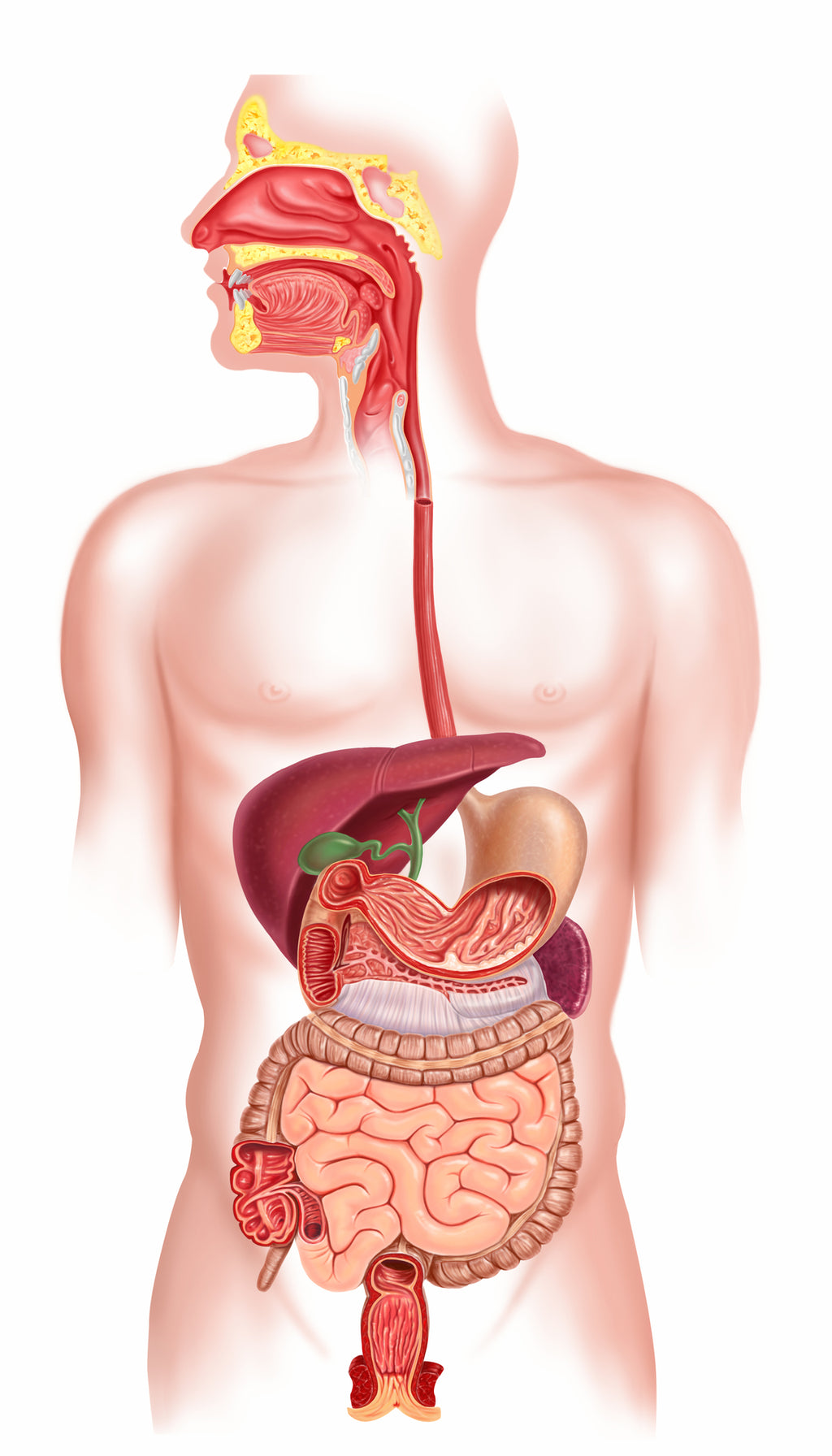

Journey To The Mouth

You, as the broccoli, find yourself speared with a fork and taken to a wild and dangerous place. The human mouth is typically rimmed with 32 bony protrusions known as teeth. Some teeth are for slicing, others for grinding, and a few for piercing. Found in the jaw are some of the strongest muscles and the strongest bone. At about 70 pounds per square inch, the back molars can more than crush most food.

As of lightly steamed piece of broccoli, you don't stand a chance. Guided by the tongue, a strong and dexterous muscle, and the only muscle attached only at one side and able to move on its own, you are guided to the incisors that slice you into little pieces. Then, it's on to the back molars that grind and crunch.

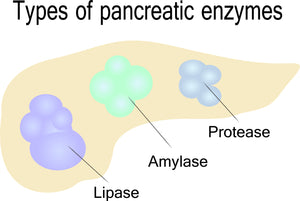

But that's not all. The salivary glands drip a mixture of water, mucus, and digestive enzymes that begin chemically breaking up you're very being. Amylase starts breaking down the starches and fibers of your being. It turns your structure into simple sugars and fibers.

Lysozyme helps break down polysaccharides, particularly those in the cell walls of many bacteria. While it doesn't work on you, some of your hitchhiking bacteria meet their end thanks to the lysosome. Some of these dangerous bacteria cause food poisoning.

There's also lipase that breaks down fatty acids and salivary kallikrein that breaks down proteins.

As we age, our digestive enzymes begin to weaken and decrease in production. It makes it more difficult to digest food if we're not chewing it up into little pieces and mixing it with the digestive enzymes. That's why our doctors often recommend digestive enzymes to help people digestive food.

You finally mix up into a ball-like mixture of food and saliva known as a bolus. Now, you get pushed down into a tube known as the esophagus... dropping, dropping until you splash down…

The Wild Ride Of The Stomach

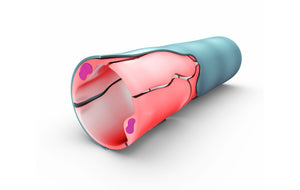

The esophagus is a long tube bridging the mouth and the stomach. But, it can become excruciatingly painful if the stomach isn't able to do the job it's meant to. It can happen if we're not chewing our food correctly, which makes the stomach work harder. Large pieces of food also damage the lining of the esophagus. Things like GERD, acid reflux, and belching all injure the esophagus when your food doesn't get digested properly.

Now, as you're dropping through the end of the esophagus, the cardiac sphincter opens up, and you splash into a seething pool of digestive juices, brimming with potent acids. Held in the stomach by the pyloric sphincter, which leads to the intestine, the stomach acts as a bag surrounded by strong muscle. You, as the broccoli bolus, get squeezed, squished, and beat up in a mix of these digestive juices.

These juices include you, the saliva and enzymes from the mouth, hydrochloric acid, pepsinogen, gastrin, histamine, and along with certain pancreatic enzymes. Pepsinogen is the primary enzyme secreted by the stomach and designed to break down proteins.

Once you dropped into the stomach, the body that ate you started producing other hormones that trigger more enzymes and hormones added in the intestine. For example, now that we ate food, our pancreas creates insulin. Other organs such as the gallbladder and liver are gearing up to take care of our food.

In the stomach, you'll be tossed around and beaten up for anywhere between 1 and 4 hours. Your durable fibers are breaking down into simpler sugars; nothing is recognizable of your beautiful florets. Although there are still some traces of your lovely green, most of what remains are tiny pieces, smaller than a grain of sand, mixed up in this acidic mix now known as chime.

If someone with reflux ate you, you would notice the swollen and irritated walls of the stomach and esophagus. Maybe you have even splashed a bit up there yourself. If they didn't eat so much food, perhaps this wouldn't have happened. And if someone with ulcers ate you, you would notice the mucus membranes worn away, leaving the delicate lining uncovered and beaten by the acids, breaking it down just like you.

Then comes the next phase of the journey as the pyloric sphincter opens up, and you enter the small intestine.

The Longest Journey: The Small Intestine

If a man just ate you, you're going to now take a 22-foot journey through the small intestine. But, if a woman ate you, you have 23 feet to journey through. As the liquid chime, you're now going through the small, two-and-a-half to three centimeter tube (about the size of a quarter) known as the small intestine.

The first thing you do is drip through the duodenum, where the body mixes all of the digestive enzymes together with new secretions. The Brunner's glands secrete mucus-rich alkaline compounds that neutralize the acids and sends your pH from about 2 to between 8 and 10.

Now, the pancreas and gallbladder release more enzymes and secretions to help break you down into smaller and smaller pieces. Proteolytic enzymes start cleaving proteins into smaller peptides. Pancreatic lipase breaks down fats and oils into individual fatty acids. And it's here that the sugars from all of the simple carbohydrates start getting absorbed.

If that person who ate you has gallbladder problems, the butter that once topped your florets isn't getting broken down. There aren't enough biles and enzymes, and this means digestion isn't happening well enough.

But that's not all. You're now running into creatures, trillions and trillions of creatures known as probiotics. Hundreds of different strains suddenly start attacking you, feeding, and helping the body to break down you, the food known as broccoli, into individual chemical components.

Then, you enter the jejunum, where your nutrients begin to be absorbed. The inner surface is thick with a mucous membrane helping to protect the sensitive villi, small projections of the intestine that help increase the surface area available to absorb nutrients.

If you take a close look at these villi, you notice they grab individual molecules of nutrients and guide them through little tiny tubes, known as passive transport systems, and move these nutrients into your blood. This is how the calcium, magnesium, and all the trace nutrients move from food into your bloodstream.

But, you might notice a problem depending on the type of food you eat. For people sensitive to gluten, this particular protein is a bully to the villi. It can wrap around the sensitive little projections and snap them right off, making it harder to absorb the necessary zinc, magnesium, potassium, and all the other nutrients we need.

People with IBS have these same villi damaged. If we didn't chew our food well, larger chunks of food move through the intestine, slamming into the tiny villi and punching holes in our gut.

Maybe up ahead, you see the remnants of processed food, junk food. You can see the little devilish chemicals breaking free to claw and bite their way into the bloodstream, leaving trails of pain, swelling, and leaky gut in their wake. There isn't much nutrition, just sugars and fillers. Not even the probiotics want to touch that.

As you get pushed through the intestine by the strong muscles, in a process known as peristalsis, you pass section after section of villi looking for specific nutrients to send them to the blood. The villi are efficient, grabbing nutrients like kids grabbing at candy. Really paying attention, and you'll notice that each of these sections is very specific and works together with other nutrients to make sure the right one gets to the right place.

Maybe it surprises you that some of the fatty oils from the butter that once covered you are helping zinc, vitamin C, and vitamin E be appropriately absorbed. As you look around, realize all of the nutrients help each other. Vitamin C helps most other vitamins and minerals, and water-soluble and fat-soluble vitamins mix together, helping each other out.

That's why we take vitamins in smaller quantities more often. The body can only absorb so much; the tiny villi can only move so many molecules at once. Our Foundation Gut formula is perfect for this.

Once the body absorbs the majority of the nutrients, you enter the final section of the small intestine. The ilium is a small, final section of the small intestine that helps absorb vitamin B12, bile salts, and any remaining nutrients that can possibly remain. It's also home of the Peyer's patches, organized lymph nodules that work as the immune's surveillance system and helps destroy foreign invaders.

The Final Leg Of Our Journey, The Large Intestine, Colon

In the last section of your journey, you arrive at the large intestine. First comes the ascending colon that starts at the right hip and moves up. This tube is a lot wider but much shorter. And it's a lot smoother; the villi are no longer present.

Off to the side, you notice a little hole—one small cavern known as the appendix. Inside awaits lymphatic tissue ready to take on any foreign bacteria and viruses that made it through to the large intestine.

There are a lot more probiotic bacteria here in this section of the intestine. In fact, it's incredibly crowded. They're munching on undigested fibers and producing gas, vitamin K, and biotin. This leg of your journey takes about 16 hours, giving enough time so these probiotics can produce plenty of vitamins and gas as they ferment and digest the last remnants of your once-lovely broccoli body.

After traveling up, you cross the transverse colon before finally dropping down into the sigmoid colon on the left-hand side of the body. More and more probiotic bacteria are breaking down the final remains of the broccoli you once were. There are over 700 different species of bacteria in the large intestine, including E Coli, which produces vitamin K for us.

Things are also drying out a little bit because one of the purposes of the large intestines is to absorb water. You're now turning brownish-grey because that's all that's left over…

And now, as you drop down into the rectum, things start getting compacted and further dried out. When everything works correctly, feces collects in the rectum and stretch receptors along the walls trigger the nervous system to begin constricting the muscles and relaxing the anal sphincter. This is the sudden urge to have a bowel movement.

But, if you delay this process for too long, the fecal matter gets harder and harder resulting in constipation.

Finally, we are at the end of our journey, where you have experienced the wonder of your digestive system. All of these components are extremely necessary in the breakdown and utilization of nutrients to have a happy & healthy body.

- Nutracare Team

Comments 0